Intrinsic Loneliness

The ontological terror that arises from epistemic privacy and the human sociability that evolved to overcome it.

This post is part of the following series:

- Software Architecture: A Mirror Of Organization

- The Three Discovery Layers of Organizational Dysfunction

- The Great Individuals: Masking Deficiencies

- Perception Overlap

- Intrinsic Loneliness

Prerequisites

Before we dive in, it is essential to understand three conditions. These are not mere arguments, but fundamental cognitive truths that underlie our everyday behavior.

P1: Epistemic Privacy

As discussed in the previous post, an individual’s unique experience cannot be fully shared; it reveals itself only through direct experience.

P2: Perception of Humanity

Humans possess the ability to perceive humanity or intentional agency in various phenomena. This is rooted in the Theory of Mind (ToM) — the cognitive ability to attribute mental states (intentions, beliefs, desires) to others. Theory of Mind allows us to interpret observed actions not just as physical events, but as the products of an intentional agent. This mechanism is the key to social interaction, enabling us to sense human intent or agency within a given context.

P3: Finiteness of Cognitive Resources

Tasks like learning, problem-solving, attention, and self-control consume cognitive resources, which are finite. This is biologically proven: consuming cognitive resources is synonymous with consuming physical energy. The brain has evolved to minimize this energy expenditure through heuristics.

Ontological Terror

According to P1, humans can never fully understand one another. We all live with a sense of Cognitive Alienation. Communication, then, is the process of attempting to bridge the uncrossable chasm between physical description and phenomenal experience—a process of Cognitive Alignment. When connected with P2, it is the act of confirming that the "intentions" we sense are similar.

But why do we communicate at all? Why do we crave a sense of belonging and seek validation if we are fundamentally wired to be misunderstood?

Imagine a situation where your experiences are never understood and you are completely isolated.

Did you hear that sound?

Walking through a forest with someone, you hear a sound like thunder. You immediately check this experience with your companion. Even without words, you look for cues—do they turn their head toward the sound? If they don't react and remain indifferent to your question, how does that experience feel to you?

You begin to doubt whether the sound was a real phenomenon or a mere delusion. For a single event, you might dismiss it as a momentary lapse. But if these unverifiable experiences repeat, you lose the very criteria for judging what is real. Eventually, you lose confidence that your perception is connected to the world—and ultimately, you begin to doubt your own existence.

This is Ontological Terror.

This is not just emotional anxiety. Ontological terror is a cognitive alarm state that occurs when an individual can no longer determine if their perceptions belong to reality. Without this "reality-check," one can no longer learn, predict, or find any basis for deciding what to do next.

Interestingly, humans prioritize confirming the "reality" of a perception before reacting to the phenomenon itself. Our cognitive system asks, "Did this happen?" before asking, "What is it?" Ontological terror is the collapse of the prerequisite for action: the assurance that one's perception reaches the world.

When do you think a person dies? ... It’s when they are forgotten. — One Piece

This famous line from the anime One Piece is usually interpreted as a narrative about honor or ethical legacy—how one will be remembered. However, when viewed through the lens of Ontological Terror, this sentence ceases to be a poetic metaphor and becomes a factual statement regarding the cognitive requirements for maintaining the human subject.

From this perspective, being "forgotten" is not a matter of social reputation, but an extinction of existence. The moment one's experiences no longer reach anyone else's perception and fail to form an intersubjective reality, the individual loses their footing as a perceiving subject. This is not mere alienation or isolation; it is the collapse of the certainty that one exists in the world.

Ontological Terror is the fear that arises when the very premise (reality) that enables action and survival crumbles. In its intensity and nature, it is equivalent to—or indistinguishable from—the fear of death. For a human being, "ceasing to exist in the perception of others" is no different from "dying."

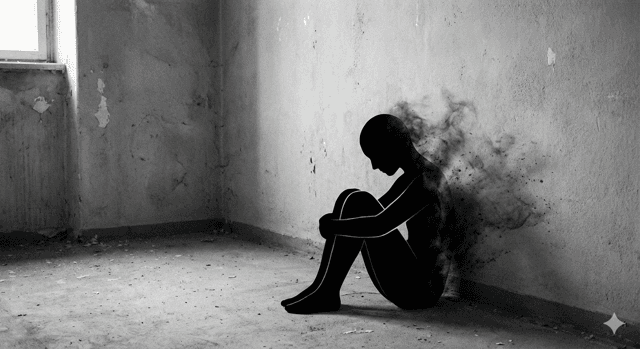

Intrinsic Loneliness

Humans are highly social — Wikipedia

This sentence has long been used as a self-evident definition of humanity. However, through the lens of Ontological Terror, this proposition must be revised. Humans do not merely 'prefer' sociality; they are 'subjugated' to it.

The fundamental reason humans seek connection is not for pleasure or cooperation, but for what we might call epistemic survival (the assurance that our experiences are real)—to prove that one's perception is not a delusion. The moment another person confirms, "I see it too," an individual's private sensation (Qualia) is elevated to an Intersubjective Reality, finally dropping the anchor of existence. In this sense, a "feeling of belonging" is not just the emotion of being part of a group; it is the psychological security of knowing that one's sense of reality is being sustained by others.

We do not feel lonely because we were born social.

We developed sociality because we were born inherently lonely.

And we have struggled, by any means necessary, to escape this loneliness—this ontological terror.

Loneliness Epidemic

Countless voiceless people sit alone every day and have no one to talk to, people of all ages, who don't feel that they can join any local groups. So they sit on social media all day when they're not at work or school. How can we solve this? — Hacker News

Never in human history have people been as constantly connected as they are today. Yet, simultaneously, never have so many people lamented such profound loneliness. This phenomenon is not confined to a specific age, class, or region. It appears among students and office workers, in cities and rural villages, and within both the extroverted and the introverted. Even in places overflowing with communication and non-stop interaction, this loneliness spreads like an epidemic.

We are all too familiar with the primary symptoms:

- Unsatisfying, long-term social media usage without a sense of fulfillment.

- Difficulty forming or maintaining bonds with neighbors or those in the immediate community.

- A contradictory desire to be heard while simultaneously hesitating to speak.

- A sense of being "disconnected" even when physically present in a space.

These symptoms are often dismissed as social or psychological issues, such as a lack of community spirit, poor social skills, or simply a lack of time. Consequently, the proposed solutions focus solely on "increasing the volume of interaction"—offering more platforms, more events, and more opportunities to connect. Yet, despite these efforts, people continue to report that they are lonely.

This loneliness is not something that suddenly emerged in the modern era. Nor is it a problem that can be explained away as a failure of an individual’s personality, effort, or social aptitude.

God

All knowing, all seeing.

Modern humanity is not the first generation to experience this structural loneliness and ontological terror. Rather, this fear has been a constant companion since the moment humans emerged as perceiving subjects. The crucial difference is that we have not always had to face this terror directly.

In pre-modern societies, humans did not rely solely on other people to validate their existence and experiences. Instead, they situated their perceptions and actions under the premise of being "witnessed by someone." That "someone" was not human.

In monotheism, God was an omniscient being and, simultaneously, an omnipresent spectator. Whatever a person saw, felt, or thought, it always resided within God’s awareness. In other words, the premise was maintained that an individual’s experience was never truly isolated; it was always connected to an external consciousness.

God functioned as a massive epistemological buffer against ontological terror. Even if their experiences were not understood by other humans, individuals could delegate the certainty that "nevertheless, this is real" to God. In essence, God acted as an infinite external cognitive resource that consumed energy on behalf of the finite cognitive resources (P3) of individual humans.

Within this structure, individuals did not have to align their perceptions with others at every moment. While social belonging remained important, the ultimate anchor of existence was fixed not in human society, but in God. Humans had not escaped ontological terror; they were merely outsourcing their loneliness to God.

Post God Era

God is dead. — Die fröhlich Wissenschaft (1882), Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

Nietzsche’s declaration is commonly interpreted as a commentary on the collapse of morality and values. However, through the lens of Ontological Terror, this statement is closer to a report on an epistemological event rather than an ethical diagnosis.

The "Death of God" signifies that humans can no longer assume an external perceiving subject who constantly witnesses and validates their experiences and actions. In other words, an individual’s experience is no longer automatically linked to an intersubjective reality, losing its final guarantee of "this is real."

In the structure where God existed, humans did not need to prove their experiences to others every single time. God was always watching, knowing, and remembering. By His existence alone, an individual's perception reached the world.

However, the role that was once outsourced to God has now returned as the responsibility of humanity.

Whither is God? he cried; I will tell you.

We have killed him-you and I. All of us are his murderers.

But how did we do this?

How could we drink up the sea?

Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon?

What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun?

Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving? Away from all suns?

Are we not plunging continually?

Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there still any up or down?

Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing?

Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder?

Is not night coatinually closing in on us?

Do we not need to light lanterns in the morning?

Do we hear nothing as yet of the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God?

Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition?

Gods, too, decompose. God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.

How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?

— Die fröhlich Wissenschaft (1882), Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

Nietzsche recognized this early on and attempted to overcome it through the ideal of the Übermensch. What he missed, however, was a single, biological truth: human cognitive resources are finite (P3).

Experiential Thinning

Technology has evolved to reduce not only physical labor but also cognitive labor (Cognitive Offloading) to overcome human limitations (P3). By bypassing the processes that cause cognitive load, technology saves our mental resources; however, it inevitably leads to the loss of the process itself—that is, the experience. While technological advancement has enabled us to do more, it has simultaneously decreased the likelihood of people sharing similar experiences or undergoing similar cognitive struggles.

That album is really great.

Before the 2000s, this single sentence implied a multitude of shared experiences. It encapsulated the effort of tracking down release news, traveling to the nearest record store, and asking about stock. Within the words "the album is good" lived the labor required to reach that judgment and the emotions felt during that struggle. Because of that labor, purchasing an album was a relatively deliberate decision. We could infer the experience the other person had gone through from this one simple remark.

Today, it is difficult to infer any concrete experience from that same sentence. We cannot know if they were truly captivated by the album itself, encountered it through a recommendation algorithm, or even which platform they used to listen to it.

Communication is the process of inferring another’s experience. However, the advancement of technology has led to Experiential Thinning, the depletion of the materials used for communication, and the cost of communicating between people has begun to rise. Communication has become a task that causes cognitive overload, leading people to feel burdened by it. Consequently, technology has gone so far as to define communication itself as a target for "optimization."

Here, we face a decisive premise that technology has overlooked: P2 (Perception of Humanity). Humans do not experience connection with others simply as the delivery or reception of information. When we encounter a message or an action, rather than processing it as a mechanical or physical event, we interpret it as the product of an intentional agent. In this process, humans perceive not only what was said but also the specific intent and the cognitive resources invested in that message.

The sense of reality we feel when we are connected arises when we discover evidence that the other person has willingly spent their finite cognitive resources for our sake. But as technology "efficientizes" communication, this evidence has grown faint.

After we sent away God—who was once the anchor of our existence and the guarantor of reality—the reality of our experience became a problem that must be verified solely between humans. Yet, technology has steadily exhausted the very materials needed for that verification.

The Loop

Consequently, the cognitive resources required for people to work (communicate) within organizations have increased, leading to widespread exhaustion and fatigue. We are consuming more cognitive energy in the workplace, and as a result, we have begun to hoard those resources in our daily lives.

People have started to shy away from active participation. Our brains, seeking to minimize energy expenditure while still receiving rewards (stimulation), have begun to favor "low-effort, high-reward" content like short-form videos and "brain-rot" media, leading to what is known as "Popcorn Brain." Instead of deep connection, people now attempt to validate their experiences through superficial metrics: views, likes, and social media reactions.

We have begun to avoid the very attempt at "overlapping perceptions" that could confirm each other's existence. The task of inferring another's experience has become a burden we are no longer willing to carry.

Yet, it seems these superficial validations are not enough. We have all fallen into a state of Cognitive Alienation, and loneliness has begun to spread like a global epidemic.

Outro

We are different.

And because we are different, we are lonely.

Because we are lonely, we had no choice but to be social.

Once, humans could entrust this loneliness to God.

God witnessed our experiences and guaranteed their reality.

But God has departed, and the seat remains empty.

Now, the only ones who can confirm that our experiences—and our existences—are real are each other.